Key Takeaways

- Organisations rarely miss industry change. They delay acting on it until the cost becomes obvious.

- Late reaction is usually driven by planning cycles, incentives, and internal ownership gaps, not lack of information.

- Faster response comes from treating industry change as an operating variable, not an annual strategy topic.

Most organisations have a predictable relationship with industry change.

First, they notice it.

Then they keep operating as if it is temporary.

Only later do they restructure, reprice, reposition, or reallocate resources. Usually under time pressure. Usually after performance has already started to drift.

This pattern is so common it is often treated as a leadership failure.

It is more accurate to treat it as a design outcome.

The default setting: organisations are built to keep going

Stability is not an accident. It is the point.

Budgets, forecasts, targets, operating rhythms, approval chains, and reporting structures all exist to reduce variation and keep the organisation moving in a consistent direction.

That design works well when the external environment changes slowly.

When it does not, the same mechanisms that protect execution begin to delay adaptation.

Industry change is not fought. It is outwaited.

What “reacting too late” actually means

Late reaction does not mean leaders were unaware.

It means that awareness never translated into commitment.

The shift was discussed. It was even accepted as plausible. But it stayed in the category of “something to watch,” rather than “something to change for.”

The organisation continued to run on yesterday’s assumptions because those assumptions still produced acceptable results.

Until they didn’t.

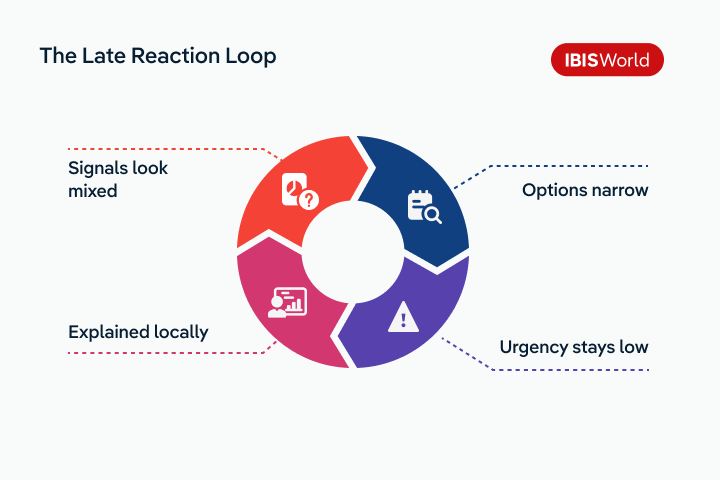

The late reaction loop

Most late responses follow a loop. Not because people are careless, but because the steps feel reasonable at the time.

Step 1: Signals appear, but look mixed

Early industry change is rarely clean. Some segments soften while others hold. One competitor moves, another doesn’t. Demand changes by region. Pricing pressure appears unevenly.

Ambiguity buys time.

Step 2: The organisation explains the signals locally

Sales frames it as pipeline quality. Marketing frames it as messaging. Operations frames it as capacity. Finance frames it as variance.

Each explanation can be correct. The problem is that none of them, alone, triggers a strategic response.

Step 3: Performance remains acceptable, so urgency stays low

As long as results remain within tolerance, the organisation’s internal logic keeps pointing toward continuity.

“Let’s see another quarter.”

“Let’s not overcorrect.”

“Let’s wait for confirmation.”

Step 4: The shift becomes undeniable, but options narrow

At the point where change becomes clear, the organisation is already behind. Response becomes compressed. Adjustments are larger, harder, and more disruptive.

The organisation acts. But it acts late.

Why the organisation cannot “just move faster”

The standard advice is to be more agile.

That is rarely specific enough to be useful.

Late reaction persists because the organisation does not have a built-in mechanism for treating industry change as actionable. It has mechanisms for treating it as commentary.

A market shift can be discussed in a meeting for six months without ever triggering a resource decision.

Not because no one cares. Because no one owns the trigger.

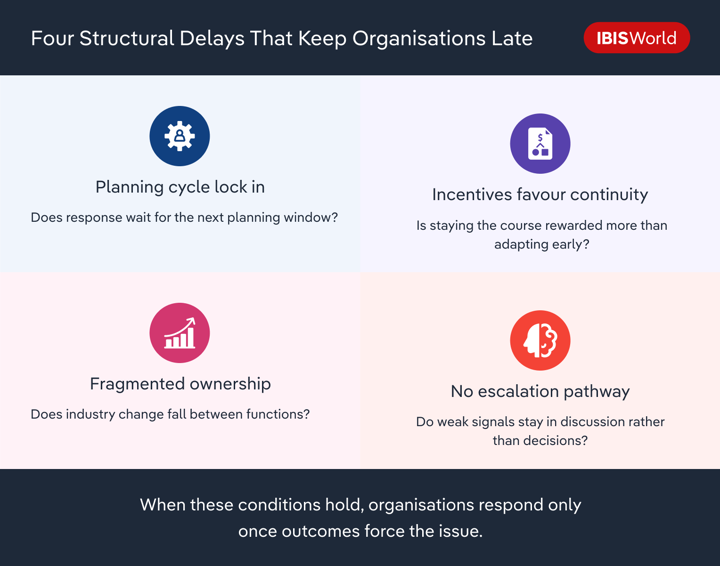

Four structural reasons response is delayed

There are many contributing factors, but late reaction is consistently driven by four structural conditions.

1. Planning cycles reward certainty, not early judgement

Most planning processes privilege confidence. Industry change rarely provides that early. The result is predictable: action is postponed until the shift is “proven,” even if proving it requires waiting until outcomes move.

2. Incentives favour continuity

Teams are measured on delivery against existing targets. Acting early often creates short-term disruption. The safest choice, personally and organisationally, is to keep executing the current plan.

3. Ownership is internal, while change is external

Industry change does not arrive inside one function. It cuts across sales, pricing, delivery, hiring, and capital allocation. But accountability is distributed by department.

If no one owns the external shift, response fragments.

4. Weak signals lack escalation pathways

Most organisations have escalation for financial risk, compliance risk, and operational incidents. They rarely have escalation for “industry conditions are shifting in a way that threatens the plan.”

So the signal stays in conversation rather than becoming a decision.

Why industry change becomes expensive to address

Waiting has a compounding effect.

Not only does the organisation lose time, it loses flexibility.

Contracts get locked in. Hiring plans progress. Product roadmaps harden. Customer expectations set. The organisation becomes structurally committed to a version of the market that no longer exists.

By the time the strategy is updated, execution is already underway in the wrong direction.

This is why late reaction often requires dramatic moves: restructures, rapid repricing, abrupt portfolio shifts, or rushed investment.

The cost is not that change happened. The cost is that response was delayed until change forced it.

What earlier response looks like in practice

Organisations that respond earlier are not more reactive. They are more systematic.

They treat industry change as an operating variable that belongs inside the same cadence as performance.

That tends to show up in three behaviours:

1. Industry context is reviewed alongside internal metrics.

Not annually, not as background, and not as a one-off research exercise.

2. Signals are connected to defined decision thresholds.

Instead of waiting for consensus, the organisation defines what kinds of external movement should trigger review, scenario planning, or resourcing shifts.

3. Cross-functional interpretation is built into governance.

Industry change is treated as shared territory. Not a sales issue, not a finance issue, not a strategy issue. A business issue.

Final Word

Late reaction is not primarily a failure of attention.

It is a failure of structure.

Most organisations are designed to keep executing even when the environment is shifting. That is why industry change is so often recognised early, discussed frequently, and acted on late.

The organisations that move sooner do not rely on better instincts. They build systems where external change can trigger internal action before outcomes force the issue.

By the time change is undeniable, the cost of waiting has already been paid.